|

| Princess Amelia from the European Magazine and London Review (Nov 1810) |

Princess Amelia (7 August 1783 - 2 November 1810) was the youngest child of King George III and Queen Charlotte.

Princess Amelia was born at the Royal Lodge, Windsor, on 7 August 1783, the fifteenth child and sixth daughter of King George III and Queen Charlotte. She was their youngest child, being more than twenty years junior to George, Prince of Wales, their eldest. She was christened in the grand council chamber at St James’ Palace on 19 September by the Archbishop of Canterbury.1

The favourite daughter of George III

Amelia’s birth came after the deaths of the two youngest princes, Alfred in August 1782 and the much-loved Octavius in May 1783. George III had been very attached to Octavius, and Amelia in some measure replaced him in her father’s affections. She became her father’s favourite child and when she was young, the King would sit on the carpet playing with her.

|

| Princess Amelia from The Lady's Magazine (1792) |

A pretty girl, Amelia grew to be tall and slender in person and graceful in demeanour. Like her sisters, her education was supervised by Lady Charlotte Finch and she was taught such academic subjects as English, French and geography as well as the accomplishments of a young lady – music, art and needlework. She became proficient on the piano and skilled at riding, her favourite pastime, but her frequent ill health prevented her from attaining as much as her sisters.

Unfortunately, Amelia’s health was never robust, and in 1798, when she was fifteen, she became ill with tuberculosis in her knee. By eighteen, she was also suffering from erysipelas, a painful bacterial skin infection also known as St Anthony’s fire. All kinds of treatments were tried including bleeding, blistering, leeches and sea bathing, as well as various remedies such as beef tea and calomel.

|

| Princess Amelia from The Georgian Era (1832) |

A summer in Worthing

During the summer of 1798, Amelia spent the summer in the quiet resort of Worthing rather than the King’s favourite place, the more lively resort of Weymouth. The Prince of Wales was a regular visitor, riding over most mornings from Brighton to see her, and sending presents when he could not visit. He wanted her to stay with him at the Pavilion, but his parents would not allow her to be moved.

Amelia was very fond of her brother George, calling him her “dear angelic brother” or her “beloved eau de miel”. She found his visits “really and truly a cordial”.

|

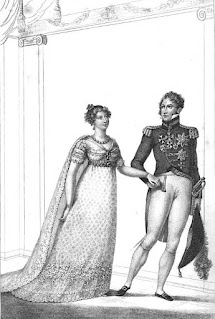

| George IV from La Belle Assemblée (1820) |

In the spring of 1799, Amelia was declared to be in a state of convalescence and a grand entertainment was given by the Queen at Frogmore on 8 March to celebrate her recovery.

Sea bathing in Weymouth

Amelia frequently visited Weymouth with her family, but her health was deteriorating and by the summer of 1799, she was not well enough to walk on the esplanade with her sisters, but stayed in Gloucester Lodge playing music, entertaining her young niece, Princess Charlotte, or making presents for her family.

The following year, she was back in Weymouth, and experienced an alarming incident. One morning she entered her bathing machine to find two men inside who refused to leave. The proprietor eventually had to frighten them out by drawing the machine into the waves and the defeated men were jeered by the crowd as they hurriedly made their exit.

|

| Gloucester Lodge on Weymouth seafront (2012) |

In 1801, Amelia was once again bathing in salt water for her health in Weymouth, attended by one of the King’s equerries, Colonel Charles Fitzroy. Fitzroy was twenty years older than Amelia and the second son of Lord Southampton, who was descended from an illegitimate son of Charles II. George III was devoted to Fitzroy and referred to him at Court as Prince Charles.

|

| Charles FitzRoy from The Romance of Princess Amelia by WS Childe-Pemberton (1911) |

Amelia fell in love with Colonel Fitzroy and desperately sought her brother George’s support to marry him. The Queen was vehemently opposed to the match. From as early as 1803, it appears that the Queen was aware of Amelia’s attachment to Fitzroy and repeatedly remonstrated with her daughter about “this unpleasant business”. Amelia never forgave her mother for her denigration of her love and complained to her brothers about the Queen’s lack of affection for her.

Amelia told her brother Frederick, the Duke of York, that she considered herself married already and began signing her letters AFR – Amelia FitzRoy – Charles’s “affectionate and devoted wife and darling” from about 1804.

Amelia’s last illness

“Remember me”

An unfulfilled legacy

|

| Princess Amelia from The Romance of Princess Amelia by WS Childe-Pemberton (1911) |

Amelia grew progressively worse and returned again to Weymouth in 1808 with her sister Mary as her devoted companion and nurse. A bathing machine was adapted for her use so that she could bathe in the sea water without effort. Other days, she went sailing, being lifted up the side of the boat in a slung chair.

“Remember me”

When she realised that her life was ending, Amelia arranged for the Court jewellers, Rundell, Bridge and Co, to prepare a ring as a final gift to her father. The ring was set with one of her jewels and a lock of her hair pressed under a small crystal window and was inscribed with the words “Remember me”. When the King visited her chamber, Amelia put the ring on his finger and her father promptly burst into tears.

| |

| George III from The History of the Reign of George III by Robert Bissett (1822) |

However, her last thoughts were for her forbidden love, Colonel Fitzroy:

In her will, she left everything to Fitzroy except for a few legacies. However, Amelia had lived beyond her means and had borrowed money from her siblings and likely also from Fitzroy. In reality, all she had to bequeath was her jewellery, and even this, George persuaded Fitzroy to renounce his claim to for the sake of delicacy and it was given to Mary instead. Afterwards, George showed some remorse that he had not been able to better fulfil his sister’s dying wishes.Tell Charles I die blessing him.3

The death of George III’s favourite daughter

Amelia died at Augusta Lodge, Windsor, on 2 November 1810. On Tuesday 13 November, the day of her funeral, every shop in Windsor was closed.2 The funeral procession was lit by torchlight and the Dean of Windsor led the service and the body was interred in St George’s Chapel at Windsor. The Countess of Chesterfield was the Chief Mourner, supported by Lady Halford, the Countess of Ilchester and the Countess of Macclesfield.

|

| Princess Amelia's coffin from La Belle Assemblée (1810) |

The King was stricken with grief at the death of his favourite child and rapidly descended into a period of derangement from which he never recovered.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) Some sources state the date as 17 September.

(2) Some sources state the date as 14 November.

(3) Childe-Pemberton, William S, The romance of Princess Amelia (1911)

(1) Some sources state the date as 17 September.

(2) Some sources state the date as 14 November.

(3) Childe-Pemberton, William S, The romance of Princess Amelia (1911)

Sources used include:

Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée, various (1806-1831, London)

Bissett, Robert, The History of the Reign of George III (Edward Parker, 1822, Philadelphia)

Chedzoy, Alan, Seaside Sovereign - King George III at Weymouth (Dovecote Press, 2003, Dorset)

Childe-Pemberton, William S, The romance of Princess Amelia (1911)

Clarke, The Georgian Era (Vizetelly, Branston and Co, 1832, London)

Hall, Mrs Matthew, The Royal Princesses of England (1871, London)

Hibbert, Christopher, George IV (Longmans,1972, Allen Lane, 1973, London)

Hodge, Jane Aiken, Passion and Principle (John Murray,1996, London)

Oulton, Walley Chamberlain, Authentic and Impartial Memoirs of Her Late Majesty Charlotte, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (1819, London)

Purdue, AW, George III, daughters of (act.1766-1857), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004, online edn, May 2009, accessed 10 Feb 2012)

Watkins, John, A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1827, London)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net

Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée, various (1806-1831, London)

Bissett, Robert, The History of the Reign of George III (Edward Parker, 1822, Philadelphia)

Chedzoy, Alan, Seaside Sovereign - King George III at Weymouth (Dovecote Press, 2003, Dorset)

Childe-Pemberton, William S, The romance of Princess Amelia (1911)

Clarke, The Georgian Era (Vizetelly, Branston and Co, 1832, London)

Hall, Mrs Matthew, The Royal Princesses of England (1871, London)

Hibbert, Christopher, George IV (Longmans,1972, Allen Lane, 1973, London)

Hodge, Jane Aiken, Passion and Principle (John Murray,1996, London)

Oulton, Walley Chamberlain, Authentic and Impartial Memoirs of Her Late Majesty Charlotte, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (1819, London)

Purdue, AW, George III, daughters of (act.1766-1857), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004, online edn, May 2009, accessed 10 Feb 2012)

Watkins, John, A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1827, London)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net