Harriet, Lady Bessborough (16 June 1761 - 11 November 1821), was the younger sister of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. She was a leading figure in society and notorious for her affairs with Richard Brinsley Sheridan and Lord Granville Leveson-Gower.

Early life

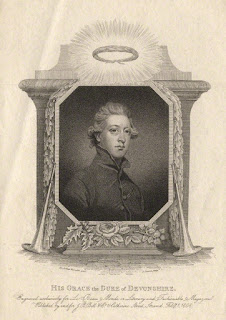

Henrietta Frances Spencer was born in Wimbledon, Surrey, on 16 June 1761, the second daughter of John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer and Lady Margaret Poyntz. Henrietta, known as Harriet, was tall and attractive, but lived in the shadow of her elder sister, Georgiana, who became the Duchess of Devonshire at the age of seventeen.

An unwise marriage

Harriet was passionately attached to Georgiana and this encouraged her to choose Frederick Ponsonby, Viscount Duncannon, the Duke’s cousin, as her husband, even though she was unsure of his character. They were married on 27 November 1780 and quickly became part of the Devonshire House set, with its dissolute habits.

Harriet became addicted to gambling and amassed thousands of pounds of debt that she could not afford to pay. Duncannon proved to be an abusive husband, desperate to get his hands on Harriet’s financial settlement, and frequently Harriet had to turn to her family for help. They had four children, John William (1781), Frederick Cavendish (1783), Caroline (1785) and William (1787).

Harriet became addicted to gambling and amassed thousands of pounds of debt that she could not afford to pay. Duncannon proved to be an abusive husband, desperate to get his hands on Harriet’s financial settlement, and frequently Harriet had to turn to her family for help. They had four children, John William (1781), Frederick Cavendish (1783), Caroline (1785) and William (1787).

Whig canvassing

In 1784, she canvassed for votes for the Whig leader, Charles James Fox, alongside her sister Georgiana, in the Westminster Election. Although their actions were similar, it was Georgiana who was ridiculed in the press, no doubt because of her greater position of popularity and importance in the ton. In the 1788 by-election, Harriet canvassed for the Whigs again; Georgiana stayed at home.

Affairs of the heart

Harriet was unhappy in her marriage and jealous of Lady Elizabeth Foster’s influence over Georgiana. She embarked upon an affair with Charles Wyndham, one of the Devonshire House set, but was prevented from eloping with him by her brother and mother. They successfully persuaded her to drop the connection before her husband found out.

But this did not stop her indulging in other affairs. In 1788, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the playwright and MP, became Harriet’s lover. The affair almost ended in divorce, but the Duke of Devonshire, with all the weight of the Cavendish family behind him, induced Harriet's husband to drop proceedings. He then insisted that the Duncannons visit him and Georgiana in Brussels, in order to avoid any possibility of further problems with Sheridan.

Years later, in 1805, Sheridan became obsessed with Harriet, causing her great distress by pressing his attentions on her in public.

Affairs of the heart

Harriet was unhappy in her marriage and jealous of Lady Elizabeth Foster’s influence over Georgiana. She embarked upon an affair with Charles Wyndham, one of the Devonshire House set, but was prevented from eloping with him by her brother and mother. They successfully persuaded her to drop the connection before her husband found out.

But this did not stop her indulging in other affairs. In 1788, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the playwright and MP, became Harriet’s lover. The affair almost ended in divorce, but the Duke of Devonshire, with all the weight of the Cavendish family behind him, induced Harriet's husband to drop proceedings. He then insisted that the Duncannons visit him and Georgiana in Brussels, in order to avoid any possibility of further problems with Sheridan.

Years later, in 1805, Sheridan became obsessed with Harriet, causing her great distress by pressing his attentions on her in public.

In 1791, Harriet and her sister were involved in a financial scandal. They had speculated in a risky share syndicate which failed. Both lost large sums of money.

At the same time, Harriet’s health collapsed. She had some kind of stroke which left her paralysed down one side and subject to fits. There has been much speculation as to the cause of this illness. It may have been as a result of a miscarriage or possibly an attempted abortion. Alternatively, it may have been caused by attempted suicide or ill treatment at her husband’s hands, which may in turn have been a response to her financial losses.

At the same time, Harriet’s health collapsed. She had some kind of stroke which left her paralysed down one side and subject to fits. There has been much speculation as to the cause of this illness. It may have been as a result of a miscarriage or possibly an attempted abortion. Alternatively, it may have been caused by attempted suicide or ill treatment at her husband’s hands, which may in turn have been a response to her financial losses.

Bath

Whist still suffering from partial paralysis, Harriet caught bronchial pneumonia, and it looked as if she would not survive. Although the Duke was on bad terms with his wife over her enormous debts, he showed compassion on her and her ailing sister by renting a house in Bath for them and all their children to live in, so that Harriet could benefit from taking the waters.

But in the autumn of 1791, the situation changed drastically. Georgiana was sent abroad by the Duke in disgrace: she was pregnant with her lover’s child. This coincided with recommendations that Harriet visit a warmer climate to aid her recovery, providing a useful cover story for the party, which included Georgiana, Lady Spencer, Lady Elizabeth Foster and the Duncannons.

They travelled to Montpellier, where Georgiana had her baby, and then through southern France and Switzerland to Italy, where it was hoped that the warm, dry air would help Harriet’s lungs.

They travelled to Montpellier, where Georgiana had her baby, and then through southern France and Switzerland to Italy, where it was hoped that the warm, dry air would help Harriet’s lungs.

Countess of Bessborough

On 11 March 1793, Duncannon’s father died and he became 3rd Earl of Bessborough. He left Harriet, who was still far from well, in Naples, and returned to London.

Lord Granville

The Duke finally allowed Georgiana to return home in September 1793, but Harriet was too ill to travel and stayed with her mother in Naples. However, Lady Spencer’s presence did not prevent her from falling in love again.

When Harriet returned to England a year later, fully recovered save a weakness in her legs which necessitated the use of walking sticks, she was embroiled in the most serious love affair of her life. This time the object of her affections was Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, a handsome young man, twelve years her junior, who was both politically ambitious and very prone to falling in love.

Lord Granville

The Duke finally allowed Georgiana to return home in September 1793, but Harriet was too ill to travel and stayed with her mother in Naples. However, Lady Spencer’s presence did not prevent her from falling in love again.

When Harriet returned to England a year later, fully recovered save a weakness in her legs which necessitated the use of walking sticks, she was embroiled in the most serious love affair of her life. This time the object of her affections was Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, a handsome young man, twelve years her junior, who was both politically ambitious and very prone to falling in love.

Harriet had two children by Lord Granville, Harriette Arundel Stewart (1800) and George Arundel Stewart (1802), to whom she gave birth in secret and then placed with foster parents. It was a source of great sorrow to her that she could never openly acknowledge these children as her own.

A volatile daughter

Harriet was an affectionate parent and worried about her emotionally volatile daughter, Caroline. She failed to dissuade her from marrying William Lamb in 1805. Lady Caroline Lamb’s public love affair with Byron, and extreme behaviour after it ended, was one of the greatest scandals of the day.

A dreadful bereavement

By 1805, Harriet’s health had started deteriorating. She wrote to Lord Granville that he would find her “quite a cripple” because she had “grown very lame again”.1

A volatile daughter

Harriet was an affectionate parent and worried about her emotionally volatile daughter, Caroline. She failed to dissuade her from marrying William Lamb in 1805. Lady Caroline Lamb’s public love affair with Byron, and extreme behaviour after it ended, was one of the greatest scandals of the day.

A dreadful bereavement

By 1805, Harriet’s health had started deteriorating. She wrote to Lord Granville that he would find her “quite a cripple” because she had “grown very lame again”.1

In 1806, Georgiana became seriously ill and died. Harriet was devastated. She wrote to Lord Granville: “Anything so horrible, so killing, as her three days’ agony no human being ever witness’d.”2

|

| Georgiana Cavendish in the "picture hat" after Thomas Gainsborough c1785-7 from The Two Duchesses, Family Correspondence (1898) |

On Christmas Eve 1809, Lord Granville married Harriet’s niece, Georgiana’s daughter Harryo. The letters exchanged between Lord Granville and Harriet at the time suggest that, though it must surely have been painful, Harriet had encouraged the match. However, she later doubted whether Granville had ever really loved her and their previous intimacy must have caused considerable awkwardness in the family.

Ironically, the Prince of Wales chose to champion Harriet at this time, abusing Lord Granville to her face for his inconstancy and throwing himself at Harriet’s feet until she could talk him back to reason!

The final years

Harriet remained a popular figure in society, but found the greatest enjoyment in her family. She often stayed with her sons and their families, and it was while she was visiting William in Florence, Italy, that she died, on 11 November 1821. Harriet was buried in the Cavendish family vault in All Saints Church, Derby.

Ironically, the Prince of Wales chose to champion Harriet at this time, abusing Lord Granville to her face for his inconstancy and throwing himself at Harriet’s feet until she could talk him back to reason!

The final years

Harriet remained a popular figure in society, but found the greatest enjoyment in her family. She often stayed with her sons and their families, and it was while she was visiting William in Florence, Italy, that she died, on 11 November 1821. Harriet was buried in the Cavendish family vault in All Saints Church, Derby.

Notes

1. From a letter from Harriet to Lord Granville 10 August 1805.

2. From an undated letter from Harriet to Lord Granville after her sister's death.

Sources used include:

Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée (John Bell, 1810, London)

Bourke, Hon. Algernon, The History of White's (1892)

Cavendish, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire and others, The Two Duchesses, Family Correspondence, ed by Vere Foster (Blackie & Son, 1898, London)

Creevey, Thomas, The Creevey Papers, A selection from the correspondence & diaries of the late Thomas Creevey, MP, ed by Sir Herbert Maxwell (John Murray, 1904, London)

Foreman, Amanda, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (HarperCollins, 1998, London)

Foreman, Amanda, Ponsonby, Henrietta Frances, Countess of Bessborough (1761-1821) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 14 Oct 2012)

Leveson-Gower, Lord Granville, Private correspondence 1781-1821, ed by Castalia, Countess Granville (John Murray, 1916, London)

All photographs © regencyhistory.net